It’s well known that the government is looking to increase the number of heat networks in the UK, but there has been little coverage of the plans for exactly how. The scale, rate and mechanism of the rollout being considered in a recent consultation is startling.

The Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) recently held a consultation on proposals to create heat network zones across the country. The idea is that these zones would then be licensed for development, much like the way the government grants rights to companies for exploration and extraction of fossil fuels in specific areas. As part of Sharenergy’s work on the Community Heat Development Unit (CHDU) project we needed to spend some time understanding the proposals and their implications for communities. We responded to the consultation, calling for community and social benefit to be at the front and centre of the Heat Network Transformation Programme.

The benefits of heat networks are clear: they can offer heat potentially at far lower costs than individual heat pumps and offer a route to decarbonise heat whilst avoiding extensive, expensive and disruptive retrofit. They can allow households to benefit from heat that would otherwise be wasted from industrial or commercial sources like data centres or – unsustainable as they are – waste incinerators. Further decarbonisation advantages are available through centralised heat storage, which offers the chance to shift times of demand and thereby support intermittent renewable electricity generation. Hot water tanks are an order of magnitude less expensive than chemical batteries and don’t require exotic minerals with dubious supply chains.

The sector has been something of an unregulated wild west in the recent past, culminating in some horrific stories of overcharging during the recent energy price spike. It’s clear that there is work for government to do here.

What’s being proposed?

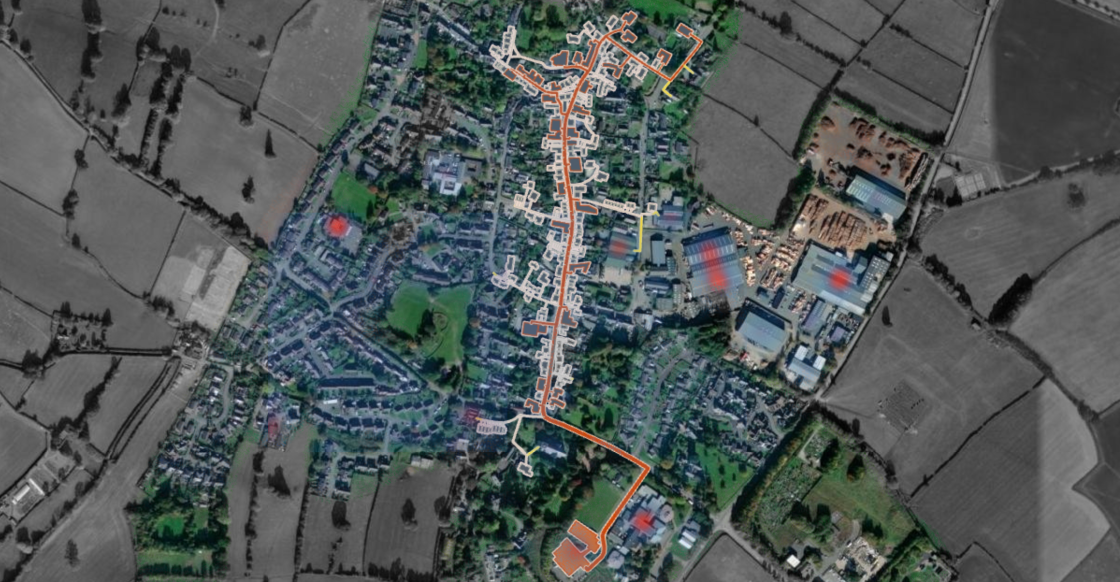

In short, the proposal that went out for consultation is that DESNZ, as “Central Authority”, will identify areas in which a heat network has the potential to offer cheaper low-carbon heat than would be achieved through every property installing an individual air-sourced heat pump (ASHP). Each such area becomes a “designated zone”, and is licensed to a developer by a local “Zone Coordinator”. The coordinator may be the local council, a regional body or combined authority, or it might be DESNZ itself. Zones are licensed through a “competitive and open process”, and four preferred commercial delivery models are given, three of which involve partial ownership by the local authority.

Within a designated zone, many nondomestic properties are likely to be compelled to connect to the heat network. The same would apply to existing communal heating systems, and new buildings are likely to be required to be “heat network ready” on construction. In the case of new developments this could mean temporary heat sources (most likely gas boilers) if the heat network is not ready to connect to the site by the time the sites are to be occupied.

As a heat network expands within a zone, the developer has the power to compel more nearby sites to connect to it. This applies both to consumers and to sites on which significant amounts of heat are generated, such as waste incinerators, which would be identified as potential heat sources by the Zone Coordinator.

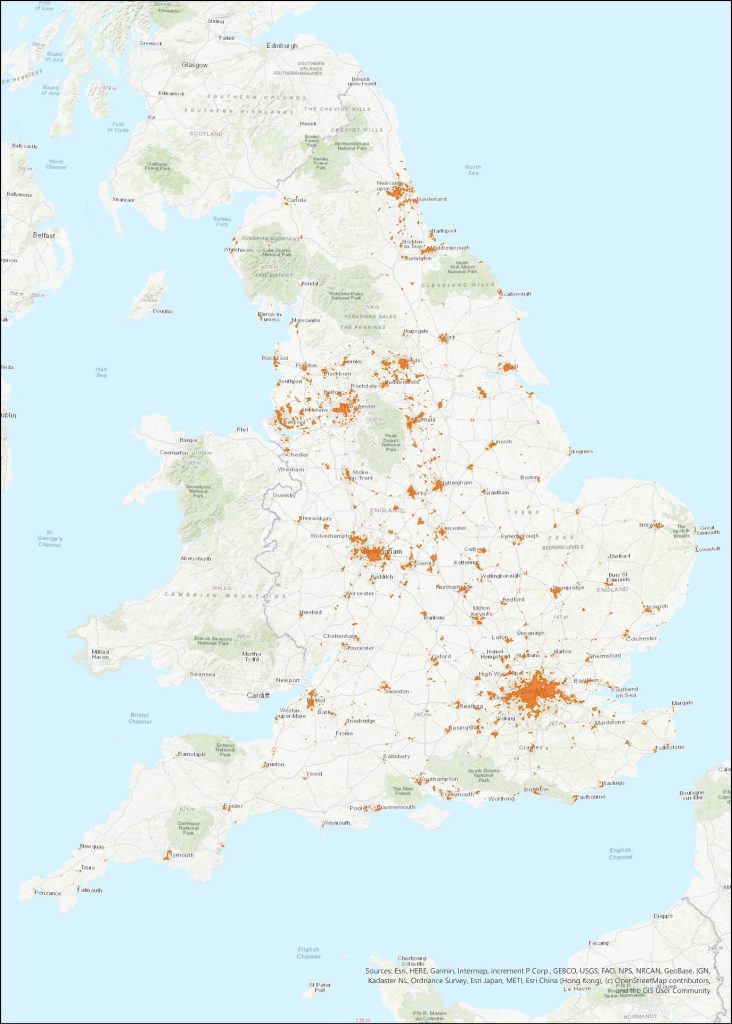

The powers being conferred onto these licensed zone developers are significant – both the powers of compulsion and also the monopolistic position they then occupy, able to set the price of heat for buildings that are likely to be reliant on the network. No figures for the number of networks or connected properties are given, but a map showing the output of a preliminary zone modelling exercise appears to show several thousand heat network zones across the country. The Committee for Climate Change (CCC) suggested that heat networks could supply 18% of UK heat demand by 2050 – equivalent to 5 million households and 387,000 nondomestic properties.

The licensing work is due to get underway next year (2025) and will require local authorities selected as Zone Coordinators to work with DESNZ to agree heat network zones. Each zone will be consulted on (the consultation suggests 21 days would be sufficient time) with the intention of developing a pipeline of heat network builds for the next 10-15 years, with each awarded through a “short competitive process”.

Our questions and concerns

We have three major causes for concern with this process, but all basically boil down to the total neglect of communities from any part of this process. Oversight (via elected politicians) and consultation are not the same as community engagement, and we’re seeing far too many cases where net zero infrastructure – whether in the form of solar farms or threats to suddenly-cherished gas boilers – is seeing its social support eroded as a result of a failure to address communities’ needs meaningfully.

The specific three questions we have raised in our response are:

What lessons have been learnt from previous experiences of licensing monopolistic infrastructure to private operators via a competitive process?

The issues surrounding the operation of the rail and water systems should give us pause for thought before embarking on more of the same to supply buildings with heat for the next 40-50 years. Competitive processes reward back-loading of costs and the loading up of infrastructure with debt. Partnership working between the public and private and/or third sector organisations could have a better chance of growing the sector and retaining wealth in our communities. We also think that underlying the whole process should be an understanding that the infrastructure will come into public ownership in the future, after an initial operational phase.

Why is social benefit not considered?

Even within a purely privately owned model, the social offers of heat network developers can vary massively. Zone Coordinators must have a mandate to be able to benefit their communities when acting as regulators. Governance should be a legitimate consideration when awarding licenses – after all, social enterprises with community purpose are already running museums, theatres, libraries and leisure centres very successfully all over the country.

What is expected to happen for residential properties?

The consultation does not anticipate any requirement for residential properties to connect to heat networks within zones, nor any obligation for heat network developers to enable their connection. Domestic properties represent 60% of our heat consumption nationally – it is very conspicuous that no provision is made for them. If it’s too politically difficult, doesn’t that say something about the process they’re proposing? The regulations should encourage, possibly oblige, developers to offer connections to domestic properties and regulate how these connections are treated. Why do half the job?

The consultation document itself is 110 pages long. Our response makes many other comments and recommendations, such as:

- Heat network operators should be subject to FoI legislation and publish data openly and regularly.

- Zone Controllers should have a ‘fit and proper’ test to apply for potential operators.

- Consumer groups should be represented in the boards of Zone Controllers, and

- New developments should be exempt from joining heat networks if they can demonstrate lower carbon heating without connecting.

The amount of infrastructure to be built under these regulations is immense, yet they have not featured on the radar of public political debate. The potential for community benefit – and indeed harm – is great. We would welcome a wider discussion of the proposals.